I’ll start with a confession: I avoid instructions. Don’t map the route. Abandon assembly instructions on sight. Collect unread tutorial emails for always.

This avoidant tendency grows out of the same root that keeps me from any time-based content like podcasts and videos, instructional or not: even with the playback speed jacked, I have no control over the sequential, durational nature of my acquisition of the content, and I can’t handle it. Who spends 30 minutes listening to ideas that can be scanned in show notes in 30 seconds? Who spends 11 minutes watching a process demonstrated in a help video before they’ve tried to just make the thing work as it seems like it ought to? One of these days, I’m going to start keeping track of how much time I spend viewing the video anyway, after trying three different things I thought would work (Lean’s “hidden factory”).

The root is impatience. It is urgency culture. Understanding this is helpful, and not just because I can work to shift the tendency from that understanding. It’s also helpful as a perspective: I tend to notice impatience and urgency everywhere, because I’m working on my own. Maybe it’s a little like noticing, after treating yourself to some special new shoes, that they are actually massively popular and seem to be on absolutely everyone’s feet.

I have been noticing it particularly in organizations, increasingly over time (urgency, not shoe trends). This makes sense, given this moment of intersecting crises. It can appear that we are running out of time in these matters and therefore cannot actually afford to carefully plan and enact long term responses. Even in organizations whose purpose does not involve trying to respond to crises directly, the crises impact their operating in myriad ways, and the clock-ticking-down prognoses are just as present as they are in organizations whose purpose is to mitigate the crises. Fuel prices, insurance premiums, workforce dynamics, cybersecurity, supply chain, and regulatory compliance, to name only a few factors, are fast-moving challenges on ominous trajectories. (Underpinning all of our crises is, of course, capitalism and colonialism.)

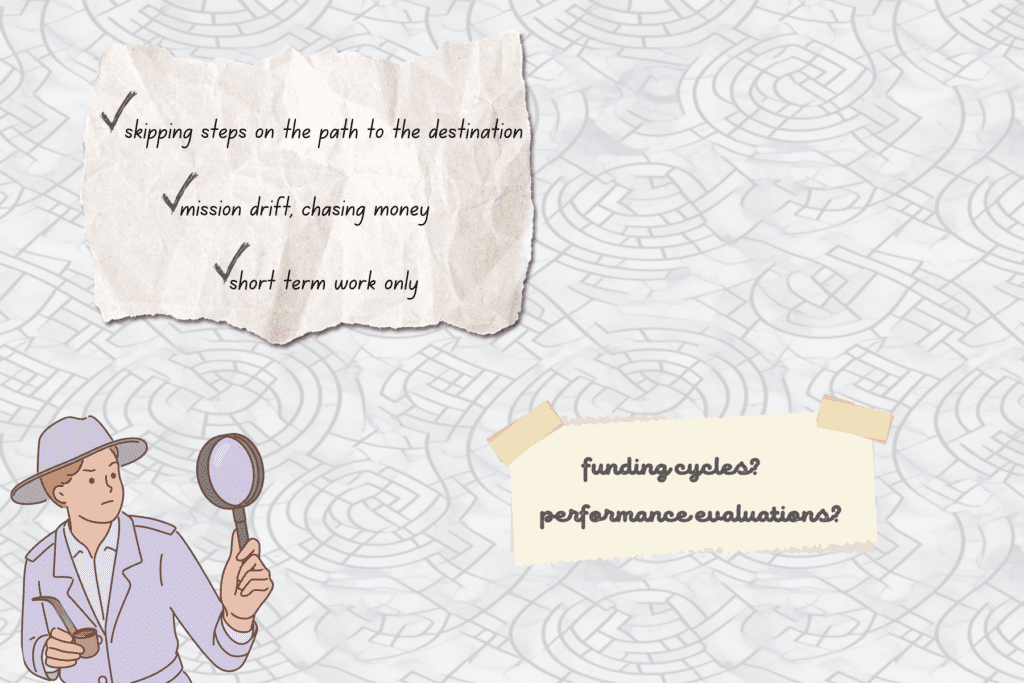

So a standard operating mode of beat the clock, often unexamined, is now ubiquitous. The trouble is, quoting my mom quoting the emperor Augustus, “festina lente” (more haste less speed). Or, tying back to Lean while staying in proverbial mode, haste makes waste! It’s a conundrum: what if the results you need quickly can’t be well produced quickly? Alas, as I continue to experience in my own life, organizations may also know this, but that knowledge doesn’t automatically curb the tendency. That’s because it’s embedded in the culture. I may have arrived in better relationship to my urgency, but if my performance in the organization will be evaluated based on quantity over quality or starts over completions or busyness over impact, I’ll need to work in that way, if I choose to remain in the organization. Or the organization may stop encouraging or rewarding needless urgency, but if it hasn’t mapped out and implemented the corresponding structural or process supports (resource allocation, incentives and performance metrics, accessibility supports, roles, workflows, policy) to enable this shift, it will either become less effective or it will continue operating in perpetual urgency. An organization may even have all of the supports and structures designed accordingly, but if core funding emanates from urgency culture, those supports and structures will be unused or hacked.

What symptoms might indicate that urgency culture is troubling your organization? Sometimes it might be the basics: problems with quality or delivery or impact, persistent overwhelm, burnout, and turnover. There can also be more insidious tells. For instance:

If you’re like me, you’ve had this article open in a tab for two weeks before finally reading it. Maybe you’ve been reading it, in parts, over a week. Maybe you’ve been feeling pressure to stop reading it because it’s not as mission critical as other work you might be putting into this time (or, if you’re reading it in personal time, it’s not as mission critical as other living you might be putting into the time). How might you overcome the conundrum of urgency culture preventing you from dealing with your urgency culture?

This will likely be as varied and individual as anything relating to motivation tends to be. For me, it might be philosophical. For instance, I have long liked to ponder time as having realities other than that of “absolute” time. The Aboriginal thinking on Dreamtime. Einstein’s notion that “time is suspect”. In some ways, it feels a bit like cultivating abundance mindset. What do I need in order to allow myself to act from this mindset? Some boundaries? Some co-conspirators?

Once you’ve given yourself permission to tackle this, there a couple of ways you might begin.

Be sure to design your Urgency Audit to capture equity and inclusion impacts, as urgency culture disproportionately affects equity deserving people, and as such will be a crucial element of your growing understanding of urgency in your organization. Highly recommended reading on this is Lydia Phillip’s “Resisting a Rest: How Urgency Culture Polices Our Work”.

Big Waves is about making work feel better, and eliminating needless urgency is such a powerful way to do that, as it changes the work on multiple levels: improving impact, reducing waste, and supporting healthy, equitable and enjoyable orientations to the work itself.